IELTS Mock Test 2024 February

- 发布时间: 07 Sep 2023

- 模考人次: 2,304,236

正确答案:

Part 1: Question 1 - 14

- 1 E

- 2 H

- 3 C

- 4 B

- 5 B

- 6 FALSE

- 7 TRUE

- 8 NOT GIVEN

- 9 FALSE

- 10 TRUE

- 11 D

- 12 E

- 13 B

- 14 C

- 1 E

- 2 H

- 3 C

- 4 B

- 5 B

- 6 FALSE

- 7 TRUE

- 8 NOT GIVEN

- 9 FALSE

- 10 TRUE

- 11 D

- 12 E

- 13 B

- 14 C

Part 2: Question 15 - 27

- 15 B

- 16 B

- 17 A

- 18 A

- 19 C

- 20 B

- 21 A

- 22 C

- 23 E

- 24 D

- 25 FALSE

- 26 TRUE

- 27 TRUE

- 15 B

- 16 B

- 17 A

- 18 A

- 19 C

- 20 B

- 21 A

- 22 C

- 23 E

- 24 D

- 25 FALSE

- 26 TRUE

- 27 TRUE

Part 3: Question 28 - 40

- 28 ii

- 29 v

- 30 i

- 31 iv

- 32 viii

- 33 insects

- 34 nectar

- 35 one third

- 36 cross-pollination

- 37 energy costs

- 38 tree species

- 39 trap-lining

- 40 A

- 28 ii

- 29 v

- 30 i

- 31 iv

- 32 viii

- 33 insects

- 34 nectar

- 35 one third

- 36 cross-pollination

- 37 energy costs

- 38 tree species

- 39 trap-lining

- 40 A

详细试卷答案解析:

Questions 1-5

The reading Passage has six paragraphs A-H Which paragraph contains the following information? Write the correct letter A-H, in boxes 1-5 on your answer sheet.

NB: you may use the letter more than once

1 . the process of the new food flavor is agreed on

2 . the reason for some natural preferences

3 . the reason why flavor has not been researched in depth in the past.

4 . the explanation of lack of consistency in sensory analyzing data.

5 . the wider benefits to the knowledge of researching flavors.

- 1 Answer: E

- 2 Answer: H

- 3 Answer: C

- 4 Answer: B

- 5 Answer: B

Questions 6-10

Do the following statements agree with the information given in the Reading Passage? In boxes 6-10 on your answer sheet, write

| TRUE | if the statement agrees with the information |

| FALSE | if the statement contradicts the information |

| NOT GIVEN | If there is no information on this |

6 . Both taste and flavor can be experienced only in mouth.

7 . Some elements in flavor involve neither taste nor smell.

8 . Ice-cream manufactures are at the forefront of the research on flavor

9 . It is possible to accurately match the brain activity to the experience of flavor.

10 . Research is being done to the controlling of the experience of taste.

- 6 Answer: FALSE

- 7 Answer: TRUE

- 8 Answer: NOT GIVEN

- 9 Answer: FALSE

- 10 Answer: TRUE

Questions 11-14

Look at the following statements and the list of researcher below.

Match the person with their opinions.

Write the correct letter. A-F, in boxes 11-14 on your answer sheet.

NB You may use any letter more than once.

| A | Givaudan |

| B | University of Bath |

| C | University of Nottingham |

| D | Firmenich |

| E | Chemical senses Institute |

| F | Linguagen |

11 . Matching brain activity and food input

12 . Use genetic modification to track flavor signals

13 . Matching textural qualities of food and sensation

14 . Identify elements in certain smells

- 11 Answer: D

- 12 Answer: E

- 13 Answer: B

- 14 Answer: C

READING PASSAGE 1

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 1-14, which are based on Reading Passage 1 below.

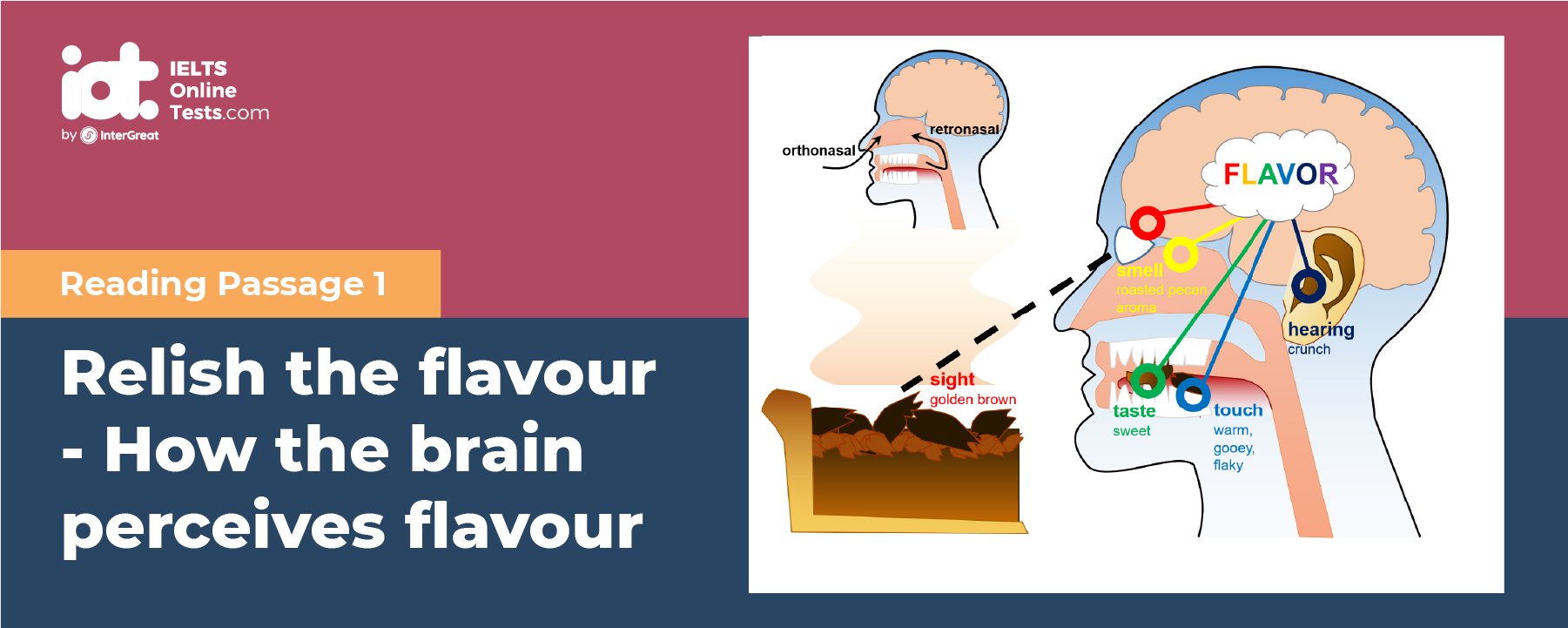

Relish the flavour - how the brain perceives flavour

A. The terms “taste” and “flavour” are used interchangeably. Strictly speaking, however, taste refers to five basic qualities: salty, sour, sweet, bitter and umami (a characteristic of protein-rich foods such as meat and cheese). Smell plays an equally prominent role in flavour but is often underappreciated. Try holding your nose and popping a strawberry- flavoured sweet in your mouth. You will taste the sweetness, but not the strawberry until you let go of your nose and the volatile chemicals from the confectionery enter the nostrils. As if that were not complex enough, irritants—for example, carbonation or the coolness of mint—are detected not by taste or smell, but by the trigeminal sense, a part of the touch system adapted for the mouth. The brain receives news about what is in the mouth from receptors—proteins specialised in picking up particular molecules—located throughout the oral and nasal cavities. Receptors for smell were identified in the early 1990s, and for sweet, bitter and umami only in the past two years (sour and salty tastes were somewhat better understood). That, says Gary Beauchamp, director of the Monell Chemical Senses Institute in Philadelphia, whose group contributed to some of the findings, is more than has been learnt about taste in the past 2,000 years. A receptor for capsaicin, the molecule that gives chilli peppers their bite, was identified only in 1997.

B. The discovery of taste receptors opens the way to mimicking, enhancing or blocking them for various desired effects—such as increasing the salty taste of low-sodium foods, or preventing the bitterness that characterises many medicinal drugs, or boosting the flavours of diets for the elderly to ensure they eat properly. But receptors are only part of the story. Nobody knows how the brain distinguishes a mouthful of milk from a bite of bread, or chicken tikka masala in an Indian restaurant from one bought at a supermarket. Although some scientists argue that the brain's response to stimuli is a simple map of the receptors in the tongue and nose, a more compelling theory suggests that the overall patterning of signals together creates a sense of particular flavours, whose attractiveness is judged in the light of previous experience.

There are no useful algorithms to measure brain inputs and outputs against subjective reports of flavour sensations. That is good news for neurophysiologists looking for work. But for flavour and fragrance companies—with global sales of flavours accounting for more than a third of the $35 billion-a-year food ingredients market—acceptable tastes bear directly on the bottom line. There is no question that flavour is the most important criterion for consumer acceptance of foods. And being able to predict what customers will like is the industry's greatest single ambition.

C. Throughout history, flavours have been coveted for their ability to increase the palatability of food and to enliven cuisine. In 408, Alaric the Visigoth's price for raising the siege of Rome allegedly included more than 1,000 kilograms of pepper. Industrial production of perfumes began in France in the 18th century to take the smell out of leather gloves. The flavour industry was a logical consequence of such developments. Extracts and essential oils such as citrus were being produced in America by the late 1700s. In 1874, Haarmann and Reimer in Germany became the first company to make synthetic vanillin (from the sap of conifers) on an industrial scale. At first, isolating and identifying gustatory ingredients proved extremely hard. Not only were analytical methods rudimentary, but the substances responsible for taste are present in minuscule amounts even in concentrated foods such as crushed raspberries. After 1950, new analytical techniques made it possible to detect trace ingredients, and companies accumulated chemical libraries that today contain thousands of compounds.

D. Depending on what a customer wants, flavours can be used off the shelf, modified or created anew, following a principle called GRAS (generally recognised as safe). It is a constant challenge to be unique, says Bob Eilerman, leader of flavour research and development for Givaudan, a Swiss company whose scientists float over tropical rainforests in hot-air balloons to find new tastes and ingredients, capture their aromas on site, and then analyse and re-create them in the laboratory. The most potent flavoured chemicals are created by cooking, says Anthony Blake, vice-president of food science and technology at Firmenich in Geneva. Firmenich, Givaudan and International Flavours and Fragrances, the industry leader in America, comprise the big three of flavour and fragrance companies world-wide. Small wonder that Firmenich employs techno-chefs, or that Givaudan dispatches analysts to ethnic restaurants hither and yon.

E. Like colourists grinding and mixing pigments, professional flavourists assemble the 50-100 components that are typical for a flavour into the finished product. Acceptability is measured using panels of expert and consumer (ie, naive) taste-testers in a process called sensory analysis. Trained testers might be asked to rate the taste of vanilla ice-cream according to standards for sweetness and vanilla flavour, whereas consumer testers simply register whether they like it. The process is an iterative one, with several rounds of refinement between testers and flavourists, until the product is deemed to have an acceptable taste.

Unfortunately, says Alex Häusler, director of flavour excellence at Givaudan, while humans provide the most sensitive testing instrument, they are not the most reliable. People are born with different sets of taste receptors and different ways of interpreting them. Think of the last time you watched somebody pour spoonfuls of sugar into a cup of coffee. Texture is a particular conundrum. It contributes substantially to the pleasure of eating, yet very little is known about it. Why is rubbery squid enjoyable and rubbery toast not? What does “succulent” mean? Since the 1960s, the food industry has devised a battery of instrument tests for desired textural properties, including poking peas with pins and bending biscuits. But theory has been lacking, and giving a carrot a whack bears little resemblance to what happens inside the mouth, where it is traversed by a multitude of physicochemical processes. Julian Vincent of the University of Bath, in Britain, is one of a small band of academic researchers who are trying to relate the results of mechanical tests to perceptions such as crispness.

F. The dynamics of flavour release—ie, the appearance and disappearance of flavour—have also resisted measurement. Researchers at the University of Nottingham, also in Britain, have developed and commercialised an instrument called MS-Nose that sucks in breath from a person's nose while they are chewing gum, for instance, and analyses the aroma molecules it finds there. Firmenich has adopted the technology in its search for better ways of delivering flavour. The approach has stimulated a good deal of interest, even though the results tend to be unique to the person tested.

Physiological studies of flavour are conducted using animals (mostly rats and hamsters) or bacteria, which have robust taste receptors. In humans, techniques such as functional magnetic-resonance imaging and positron-emission tomography—currently being applied to problems as diverse as working memory and lovesickness—can reveal patterns of electrical activity swishing around the brain in real time, says Dr Blake. The idea is to get a person to eat something and see what parts of their brain light up. But the technologies are not yet sensitive enough, nor are the ways of analysing the data meaningful enough, for the methods to be useful in studies of flavour. An alternative approach, says Monell's Dr Beauchamp, would be to focus on specific genes in animals and alter them to track the pathways that the brain uses in integrating signals from the receptors.

G. At present, finding the right enhancer or blocker for a given receptor means looking at thousands of compounds, a task better suited to automated testing than the caprices of the human tongue. Senomyx, a young biotech company in La Jolla, California, intends to use such a technology, called “high-throughput screening”, to test legions of compounds against taste and smell receptors. Whether the technique will prove more successful in food science than in pharmaceutical research and development, where it is widely used but has not yet produced a blockbuster drug, remains to be seen. Another biotech firm, Linguagen of Paramus, New Jersey, is also bringing modern science to bear in the search for flavour modifiers, particularly bitterness blockers.

H. The mouth is the portal of entry to the gut, and taste is the final arbiter. Innate aversions to sour and bitter substances—caffeine, nicotine, strychnine, for example—and a liking for sweet and salty ones reflect the wise choices that humanity's ancestors made in a hostile environment. Beyond these protective and nutritional reflexes, however, taste preferences are largely a matter of culture and learning. The taste system is reasonably compliant, says Tom Scott, a neurophysiologist and dean of sciences at San Diego State University in California. Cultures are kept distinct by cuisines, and cuisines are distinguished by taste.

But cuisines, like continents, have a habit of colliding. Ten years ago, few Americans cared for raw fish. Now they eat sushi almost as avidly as the Japanese. Moreover, “acquired tastes” often involve complex contradictions that play tricks within the brain. How else do you explain the liking for strong-smelling cheese or the East Asian fruit called durian that is so redolent of vomit that it is banned on public transport in some countries? Other effects resist reconciliation, like the unbearable sweetness that artichokes lend to wine. Flavour appears to belong to a family of subtle perceptions—such as recognising a voice or telling faces apart. But how does the central nervous system process all the information needed to make these fine-grained distinctions? The answer should help to develop cheaper and safer flavour compounds, as well as to perform tricks of alchemy such as turning tofu into steak. More fundamentally, identifying algorithms in the brain that transform taste into flavour, and comparing them with how people process complex sounds or tactile sensations, might reveal something about how perception really works.